DAVID THOMAS: PERE UBU – WORRIED MAN BLUES

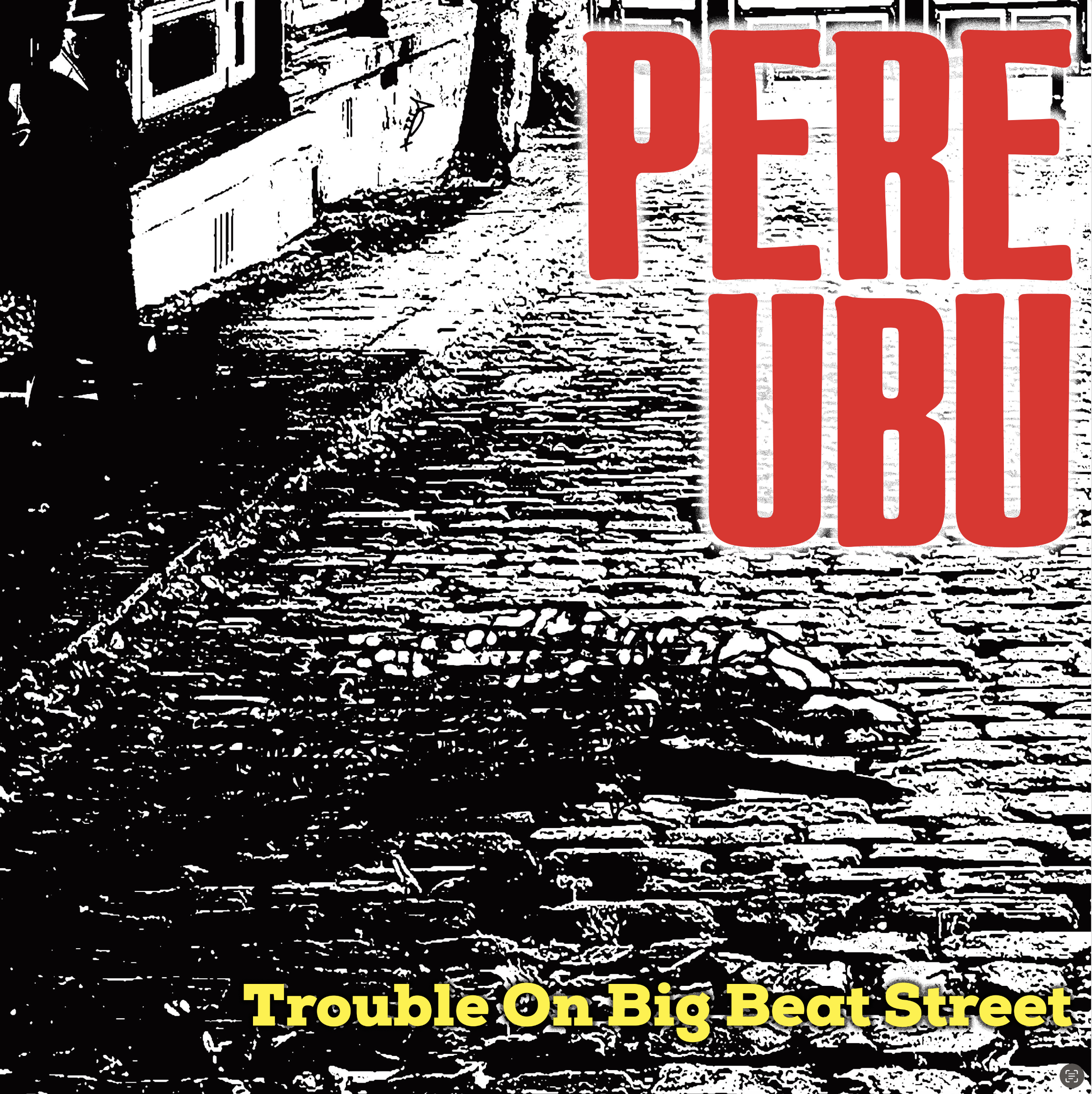

The experimental art, noise group release the next chapter of their journey following 2019’s ‘The Long Goodbye’, which waved off the band’s first phase following a grand total of 18 studio albums. Pere Ubu now begin a new chapter and, almost 4 years on from their last album, founder and songwriter David Thomas brings together a fresh lineup to tell this story. The new record, ‘Trouble On Big Beat Street’, fuses noir-style cool jazz and Southern blues with hyperactive dance-pop rhythms and nonsensical lyrics that takes particular inspiration from David’s love of Beach Boys’ collaborator Van Dyke Parks and his definition of ‘The Song’. I speak to David about Van Dyke’s influence, driving around the blues trail in America, visa red tape and what’s coming up next for the band.

How long had you been working on this album since the last one?

Not that long. I think we started it last January; probably finished it somewhere over the summer. It takes a long time once we finished it to get it out. The last album, ‘The Long Goodbye’, was meant to wrap up all of the stories that Pere Ubu has been recording that made up the albums over the last number of years. I knew that we were going to start the ideas that we would start on the next project; the next chapter.

I thought about that for a while and in the end I settled on what Brian Wilson had showed back when he was doing ‘Smiley Smile’. He had just recorded ‘Good Vibrations’, which was still considered to be the perfect rock-pop single, and he knew that he had to create the perfect album for it to go on. He teamed up with Van Dyke Parks, started on it and received a lot of derision from the other members of the band, The Beach Boys. He had some problems with drugs and emotional issues and in the end, he abandoned the album/had it taken away from him. And in that process, he had in fact created the perfect album because, along the way, he recorded countless alternate versions of the songs with sections of the songs. I have many, many, many bootlegs of all of those, or most of those sections.

So he indeed did create the perfect album because it only exists in the imagination of the listeners to all of those bootlegs – ‘you’ve put this section because, oh, this section should go with that section and oh no, there’d be a third thing here’ and on and on and on, so you the listener creates the perfect album. Now later he did record ‘[Smiley] Smile’ with Van Dyke and in that this, ‘that’s this or that’ doesn’t really enter into the picture. I wanted to go about creating the perfect way of working, which would be as much as possible to create the space in the imagination of the listener.

You’ve been influenced by Van Dyke’s work for a long time. Why did it take you 53 years to define that?

Because things don’t all happen at once: it takes time and things need to be settled on. I started in on the current project back in the ‘90s with the band Dave Thomas and Two Pale Boys. The Pale Boys were assembled as the shock troops for Pere Ubu: I would begin to prepare Pere Ubu and my working methods and personnel for what eventually came. I worked over the long term; I’m not in the pop business: I assemble things step-by-step and proceed step-by-step.

Can you explain the recording process in how the band played each song once?

We got together; we did performances over our live streaming show DPK TV. We did some shows at Cafe Oto, a sort of improv club in London and we would just get together and create – that’s how it happened. Some of the songs were pulled from the Cafe Oto sessions; many were pulled from get- togethers for live broadcasts, live concerts on DPK TV and because I recorded everything, I took those elements and corrected them when needs be and then added some things here and there. That was basically it.

The tracklist is made up of 17 parts with the CD format. The extra tracks on the CD – what’s the significance of including those and did you debate about including them at all?

We had to have the album out on vinyl. I’m not a big fan of vinyl but there you go, lots of people are. On vinyl there are time limitations: anything more than 20 to 23 minutes is really not good quality. I chose the 10 songs that would be the album, that would go on the vinyl release. Other various people in the band were concerned that the extra 7 tracks would just be lost and well, at that time, that’s what was gonna happen. Maybe one or two would show up somewhere along the way. But there was quite an impetus from everybody else to include them on the CD. Now what we did with that was that we gave the [record] company the right to put up the 7 songs on the CD, but they remain our property; they can’t do anything else with them. And they can’t charge more for the CD, because it’s got 17 songs. That was how we handled it. I didn’t particularly want to do it, but there really was a very strong feeling that they couldn’t be lost.

We had to have the album out on vinyl. I’m not a big fan of vinyl but there you go, lots of people are. On vinyl there are time limitations: anything more than 20 to 23 minutes is really not good quality. I chose the 10 songs that would be the album, that would go on the vinyl release. Other various people in the band were concerned that the extra 7 tracks would just be lost and well, at that time, that’s what was gonna happen. Maybe one or two would show up somewhere along the way. But there was quite an impetus from everybody else to include them on the CD. Now what we did with that was that we gave the [record] company the right to put up the 7 songs on the CD, but they remain our property; they can’t do anything else with them. And they can’t charge more for the CD, because it’s got 17 songs. That was how we handled it. I didn’t particularly want to do it, but there really was a very strong feeling that they couldn’t be lost.

Did you know what the main tracks were going to be?

It took me some time. I had 17 songs and I had to get it down to 10. I knew what the times were and I figured 10 songs is generally it. Some songs are obvious; others literally up until a few minutes before I sent it to the mastering engineer, I changed one of the songs, one of the 10. It took some time to sort through it; I was interested in the 10 songs chosen specifically telling the story that I wanted to tell and it was a very hard decision for some of them.

Do you mind if we talk about some of the tracks and what they’re about? For instance, what’s a ‘moss covered boodongle’?

I’m afraid I’m not really very good on that sort of thing. When I go about writing songs, I write a series of stories or I write one story from that story. I write the songs and sometimes there’s one or two songs per story and, other times, the whole batch of them is about that story.

“I’m not in the pop business: I assemble things step-by-step and proceed step-by-step.”

‘Worried Man Blues’ – you were telling a story at the beginning of that. Is there anything that influenced you with that specific track?

Yeah, that all derives from when I would just drive around in America. When it was particularly a time to write something, I would just spin off in the car and go places. That particular event comes from hours exploring US 49 in Arkansas and [I] crossed over the Mississippi at St. Helena: US 49 intersects Highway 61 in Clarksdale and Highway 61 and US 49 intersection is the crossroads that Robert Johnson and all kinds of blues people sang about. Now at the crossroads there is a Laundromat on one corner and across the street is a Popeyes fried chicken restaurant. So I just made the story, you go into the Popeyes and Bob Dylan and Alan Lomax are behind the counter; Muddy Waters is the manager and he’s bussing tables. You pull up to the speakerphone order menu and Howlin Wolf’ “how, how, how?” [is there]…that’s the story I came up with to describe my feelings about that event.

You included jazz and blues elements throughout the album. Was that a conscious thing because of the new lineup with Andy Diagram?

Each get-together we would improvise and sometimes it came out one way and sometimes it came out another way. There’s all sorts of things that never worked out and there were 17 things that did work out. We just created.

What happened with the lineup – Andy Diagram, Alex Ward and Jack Jones?

I ran across Alex because we have this live streaming show, DPK TV: people send things in and he had sent in a cover he performed of one of my songs, ‘[The] Long Rain’, and it was really good. I sent him a message saying, “Do you want to be in the band?” He’d been a lifelong fan and he said, “Yeah! I’d like to be in the band.” So he was in the band. Andy, as you know, I’ve worked with for decades in The Pale Boys; he’s been in and out of various versions of Pere Ubu at various times and I was interested in his input. So that’s how it came together. Jack Jones is just somebody I…

…met in a pub apparently?

Well, yeah. That’s literally true. Jack Jones is a fake name for somebody who doesn’t want to be identified.

You’ve got the Crocodile and Disasto tour dates this year including London and there’s US dates with Mike Watt and FaUST. What is you relationship with Mike Watt?

Mike and I are longtime friends. We’ve done some work together years and years ago. We would run into each other on the road and I’ve always enjoyed his work, his band, his performances.

Why were certain band members unable to tour in the US?

Because of the US visa restrictions! We started the process a long time ago. We were advised that we allowed plenty of time, but the time ran out, and basically it involved me spending $10,000 on the off chance on the best-case scenario of five days’ free time at the end of the process and that was just an impossibility; it just was not going to work. We’re going to keep trying for the US ban but now instead of seven months, we’re gonna leave nine months before we do leeway time – it’s just maddening.

It’s given you the opportunity as you said to ‘make Pere Ubu outside of America’…

The quote-unquote English band is Pere Ubu and I’m not devising an American band, but I’m working with some people who lead their own bands and we’ll create something pretty cool. I’ve worked with them all before so I know what I’m doing.

Your radio show, ‘Stay Sick, Turn Blue’, you started recently and interviewed Van Dyke Parks. What else can we look forward to? Who else have you got lined up for interviews?

We’ve got Mayo Thompson coming up next talking about psychedelics and Texas in the ‘60s; I’d like to interview Henry Rollins.

You released the ‘Nuke The Whales’ boxset and also have a Record Store Day release?

Yeah, well, that was running through box sets. I think we’ve completed them all now. So yeah I enjoy the process of preparing those things. ‘Ray Gun Suitcase’ is finally gonna come out on vinyl. As I said, I’m not a huge fan of vinyl but people like the stuff so that’ll be good to have.

Is there any other news on the horizon for Pere Ubu?

We’re always working; we’re always planning and devising things. We’re getting offers in for things around Europe over the summer and into the fall, so I imagine some of those will happen. Every day I fall further and further behind and we just keep plugging away and trying to get one thing done after another really. Hopefully we’ll have some more things after June in the UK. We’ve been wanting to do some more small places improv and maybe starting to work on the next album. We’re always on the lookout for something where we can just show up and play as opposed to making a big production with all that involves, which is fine, it’s just tiring to do the big production stuff. We’re looking at putting a little show together in Margate. But again, every day I fall further behind. It’ll show up some of these days.

Pere Ubu’s new studio album, ‘Trouble on Big Beat Street’, is out now and the band play the UK in June.

Photos © Brian David Stevens.

© Ayisha Khan.

ROD ARGENT: THE ZOMBIES – HUNG UP ON A DREAM

After a three-year delay caused by Covid and illness, The Zombies finally release their new studio album, ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’, eight years on from their last release. Over half a century after their highly influential yet commercially unsuccessful album, ‘Odessey & Oracle’, the new record follows the band’s classic blueprint whilst incorporating new elements to their sound with the help of a strong new lineup and production team. Following The Zombies’ live stream from Abbey Road studios in 2021 during which they performed some of the new tracks for the first time, they play SXSW festival, also premiering a new feature film entitled ‘Hung Up On A Dream’ – a retrospective documentary of the band that leads up to its current phase. After interviewing vocalist Colin Blunstone in 2021, I now speak to band co-founder and keyboard extraordinaire, Rod Argent, about the new album and tour, recording with John Lennon’s Mellotron, constructing The Zombies’ most commercially successful single to date and what it was like being stranded in the Arizona desert for five hours.

Congratulations on the new album. You played at Abbey Road studios in 2021. What did it feel like emotionally to be playing there again 50 years after recording ‘Odessey & Oracle’ there?

I’ve got some really lovely memories of Abbey Road. In fact one of the lovely memories I’ve got is all this stuff I did with Argent my second band; a lot of that was done at Abbey Road as well. We got in touch with some of the most wonderful engineers for ‘Odessey & Oracle’: working with people like Jeff Emerick and Peter Vince was just a joy. They were very special sound engineers and the whole thing about Abbey Road is that perfect combination of old school and experimentation; certainly during the 60s, you had the best of both worlds. It felt like just being there yesterday; so familiar, because I’ve actually done quite a few things at Abbey Road. The ‘Odessey & Oracle’ album was the first time that we’d been in a situation where we produced our own album; we were in complete control of how everything should sound. So it was a very happy experience all around and the help that we got from the engineers there was terrific; they were always so friendly. Nothing was hard; it was lovely to just revisit.

And also you played some of the new album tracks, was that the first time you had played those?

It was and that was scary – really scary. Because like everyone else we’d just been through COVID; we hadn’t played for two years. I’m not sure that we could even get together and rehearse before we did it. We just walked in and played the first couple of tracks on the live show. That was very hairy. But we settled in after two or three tracks and then started to really enjoy a more comfortable experience – it was lovely.

The flowers in ‘Time of The Season’ were very strange…

It was very strange and was supposed to be a surprise for us, so we had no idea what was coming.

Can you share some of your memories of the 50th anniversary of ‘Odessey & Oracle’ tour?

Initially it was Chris White’s idea – we hadn’t really played for many, many years – that we should get the original guys back together again and do one concert at Shepherd’s Bush in 2008. We agreed to do that and we thought it was going to be quite a small, intimate affair but I very much wanted that, if we were going to do it, we should actually do it by reproducing every single overdub and note that was on the original album. We also got our current incarnation, everyone from the current band as well, working on those shows so that we could double up and use every harmony that was on the original album. We got Darian Sahanaja (Wondermints) who knows the original Mellotron that I did, better than I did, and he did the most wonderful job playing the parts; we even got Chris [White’s] wife to tape some of the high falsetto that I did on the original album, because we had more tracks than the original four tracks that we used to record back in the very early days. It was a very happy experience.

It sold out completely at Shepherd’s Bush; it turned out to be a three-day experience. But I remember an hour before we went on really getting scared: I thought this could be the worst night of my life because if it doesn’t work – we only had one rehearsal – it’s just gonna be awful and I’d want the place to swallow me up. Our manager of the time came backstage and said Snow Patrol and Robert Plant are here. Oh my God! I hope this is not a disaster if it doesn’t work. Someone said Paul Weller’s lining up outside in the queue and it’s raining. I said, “For God’s sake bring him in!” He came in and was absolutely delightful; this makes panicking worse. But I could tell within the first 10 minutes on stage that this was going to work beautifully and we had the most glorious night. So one night turned into three and then people started talking about us reprising it. Paul Weller had tickets for all three nights and bought us some wonderful champagne. I remember him saying, “That was really fantastic, but don’t keep doing it will you?” I completely agreed with that. But somehow we found ourselves doing a reprising the following year touring around the UK, and then the American management said we’ve got to mount this in America. I remember us saying we’ll do it; we’ll make this the 50th anniversary celebration. This was two or three years later and that will be it; after that year we won’t ever do that, but we’d dedicate the year to that. We did a big tour of America and Europe as well and it was hugely successful. We had this big entourage with us – 15 people on stage – because as I said, we wanted to reprise every single note from the original album and I think that we did that really successfully. So it was a lovely experience, but that was enough. That was more than 50 years ago now.

Why did you postpone your UK tour dates?

We couldn’t finish [the album] until COVID was over because it was very important to us to all be in the same room together in a way that we used to record many years ago, so that all the musicians can bounce off each other. I thought that was very, very important and that it was a self-produced album. I produced it with Dale Hanson and Mark was our live sound engineer; we had a ball producing it. So after COVID allowed us all to get back in the studio again, we got everything finished. It was a year before the release of the album because the management company had to get the right record company, do all the procedure that has to go into a record being finished off and mastered. We got that all in place. It was driving me mad that it couldn’t come out.

I also had to have a small operation on my eye. This UK tour that we’re doing now is the third attempt of the original tour. We haven’t played in the UK for so long. We just did 75 gigs last year in the US and Europe. This is just a postponed version and we finally got there. But it was because of various health things and then COVID came onto the scene as well: a couple of guys got COVID and then Colin and I got COVID. It’s just this weird time that everybody’s been through.

You’ve got SXSW coming up and you’re premiering a feature documentary there?

I’m really looking forward to SXSW, that’s where the album is going to be premiered. We’ve played there before. The first time I played it I was very worried about that as well. I thought, “Oh my God! The night we’re playing, Prince is virtually next door.” We had a great time; it went down stupendously well. What was a real factor in part of the Renaissance that we’ve recently had in America was just extraordinary. We’ve played really big places in America now. When we first went over there, we were playing to just a handful of people down south. Now places are rammed and we can have audiences of thousands, which is great. I’m really looking forward to SXSW and I’m glad the album is being premiered there.

I’m really looking forward to seeing the documentary but because we were managed so badly when we started, there’s almost no live footage of us through this, especially in those early years. I was wondering how it would turn out. The [director] was very committed though; Robert Schwartzman [is] very pleased with what he’s got. Our management was very excited about it because [SXSW] have to see the film and agree that they want to premiere it there, so they must have reacted really well to it. I’m crossing my fingers.

You were more commercially successful in America, do you see the resonance of that today?

The extraordinary thing is in America we always have a young component in the audience. It’s not people that have just followed us from the old days; we have people of all ages in the audience. Thank God for that – that’s great. The energy you get back is fantastic. Someone did an algorithm looking at all the streams we get online and unbelievably most of our streaming audience are between the ages of 22 and 37, which I thought was absolutely amazing. So we have got a young audience as well as people that have followed us all the way through.

Is it retrospective, covering your whole history as a band? Did they talk to some of the other band members from the original lineup?

Yeah, absolutely. There’ve been many, many hours of filming and us talking for very long periods of time. It’s called ‘Hung Up On A Dream’. Robert Schwartzman is an enormous fan of ‘Odessey & Oracle’. That was his primary feeling about it, but he’s also a musician and he supported us on part of a tour and took some live footage as well of some of the things that we’re doing now. He got much more interested in what’s happening now. I’m hoping it’s going to be as full a picture as possible. But yes, certainly he’s talking about the early days and a lot of coverage with Chris and Hugh [Grundy]. Sadly, Paul Atkinson is not with us anymore.

“When we first went over to America, we were playing to just a handful of people down south. Now places are rammed and we can have audiences of thousands”.

How did you get to grips with the Mellotron when you found it in the studio and how has it shaped the band over its history?

It became a very important part certainly of ‘Odessey & Oracle’. It was only there because John Lennon we believe was the guy that left it behind; The Beatles that just recorded Sergeant Pepper, walked out of the studio and a week later we were in there and I just used it. I just leapt on it really; at the time I thought this would be a great way to fill out some of the songs and we couldn’t afford an orchestra because we had a very small budget. So this would be a substitute, but it was much more than a substitute, because it has a sound of its own. In the end that was much more characteristic and interesting than a score or having someone score for us orchestral parts; it became a very personal contribution. And like on ‘Care of Cell 44’, everything was done very quickly. We didn’t have time to do an off-session set. Usually one or two passes with the Mellotron; goodness knows why it was so successful, but it did work artistically successfully. I think that some of the engineers there – Jeff Emerick and Peter Vince – were playing a big part in that because they got such a beautiful sound out of it immediately. Because we had to record ‘Odessey & Oracle’ so quickly, the tracks had a real freshness about them and all that went to add to the success of how the album was recorded and how it turned out. The whole experience was really good; the Mellotron is on half the album and I became one of the first people to use a Mellotron substantially on an album, but it wasn’t through any doing of mine – it was just because it was there.

Did you use it on this new album?

No. The whole thing about this album is that we’ve never been a ‘vintage band’. The only reason that I’ve been doing this for 20 years, this incarnation, is because I want to do things for real; I want to look forward and I want to create and go and get the energy, excitement, enjoyment and satisfaction that I get from creative writing and playing with such a great band now.

Now digitally there’s limitless tracks you can record with, but it’s interesting how you retain the same way of recording back then as a live band performance.

It’s not the question of us still doing that. I’ve produced loads of albums, for instance, I produced this album that sold four million [copies] around the world and that was done in a completely layered way. I’ve been through every form of recording and producing. But it was particularly with this album – because we were coming off that tour in America where I don’t think the band ever sounded so good and we just loved the way that the band listens to each other, the way it reacts with everything that’s going on – that we wanted to bring that approach; look back to the way we used to have to record, because there was no other way in those days, and reinvent that for ourselves. So that’s why we didn’t want to do anything remotely on this album. We wanted to wait until everyone could be in the studio together and try and capture that magic of a performance, which somehow the sum is greater than the parts.

When you work in this way you go to the old-fashioned way of recording; you’re responding to Colin’s guide vocal. He almost has always had the lead vocal, apart from ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’ where we swapped vocals. It means Colin sings slightly differently because he’s reacted to how we are playing; each member of the band reacts differently to what each person is playing. We just minorly adjust what we’re doing at the time to what you’re hearing. It’s a very exciting way to do it and a much more enjoyable way to perform and record; we wanted to get that and the band is good enough to do that. You have to have a good band to do that. We didn’t use any clip tracks; we just did things as we used to in the old days. That was a very conscious decision, to go back to that way of doing things and we found out that very often – like on the track ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’ – that was pretty much a live vocal. We kept it. We didn’t turn our back on technology at all; I’ve got all the latest stuff in my studio. And actually strangely enough, the studio was acoustically designed by John Flynn who did the Abbey Road studios. So that was a lovely association. It means that each track was recorded in its basic form in about four hours. It meant that you might do say, three or four tracks where you felt you were approaching what was really good, but it didn’t really have any sort of magic about it. And then suddenly, something will click and everyone for a few minutes is on the same wavelength; you listen back and think that’s got something special about it and you can’t quantify what that is. But it was a process that we enjoyed very, very much indeed.

“I became one of the first people to use a Mellotron substantially on an album, but it wasn’t through any doing of mine – it was just because it was there.”

There’s a track called ‘Rediscover’ where we were on tour with The Beach Boys and I just fancied writing the first part of the song – just the eight bars – as acapella vocals and do it with dissonance and some unusual voicings, because I’ve listened to The Beach Boys and really enjoying their set. I did that just for the first eight bars and then the song develops and goes into a more conventional thing. So we laid that separately, that first eight bars, because I had one to four harmonies on it. I had to tell people ‘Could you sing this?’ and then ‘Could you sing that?’ But apart from that it was live. The vocals on the rest of that song for instance – they sound really cool – were just three or four of us around one mic, going back to an old way of doing things.

When you’re songwriting, how does that relate to when you’re writing for Colin’s vocals? Does that ever come into your mind?

It always comes into my mind. We’ve been friends since we were 16-years-old and I’ve been writing my songs for Colin and his range and the characteristics of his voice; I know it so well now that I have a pretty good idea. I’m not always right: sometimes a song that I think will be so easy for him and comfortable doesn’t turn out to be and another time I think this is gonna sound great in his range. I know when he gets a certain edge in his voice; a certain pitch, I might think he’s gonna have a little bit of trouble with that and he’ll just be all over it and great. With ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’ it was pretty much one of the first takes that we did. Colin always says he grew up learning to sing my songs and I grew up learning to write for Colin’s voice. So that’s something that helps us, but it’s just as exciting. When we start the process of the song, if I can get excited about an idea, I’ll work it out in its primitive form by myself – just voice and piano – and then I’ll get Colin round and see if he likes it and if it sounds good with his voice and suits him; almost always the key is correct. We’re working from there and then we play it to the band. If it really starts happening with the band then it’s just really part of a very exciting process and very, very satisfying. That’s what we’re doing.

Can you tell me about your argument with Colin when you were recording ‘Time of The Season’?

That was quite funny. The track had been recorded with a guide vocal but Colin was putting the master vocal on. He was getting a bit fed up with it; he was looking at the clock and we’ll come to the end of the session. But I kept saying, “Can you just push that note a little bit or that phrase? It needs to be a bit like this.” And he said, “If you’re so fucking good, you come and it!” And I said, “Colin, come on.” But the whole thing about ‘Time of The Season’, when we did the main track not the lead vocal, we did what we rehearsed and the harmonies that we rehearsed and it sounded great. Jeff Emerick got the most fabulous sound out of the Tom Tom and bass drum; the “boom, boom, boom” and putting a backbeat to the side – “boom, boom, boom, clap, clap” – that was it really but it still sounded good. Then we had half an hour left on the session – and this is a typical thing that happens on ‘Odessey & Oracle’ – I said to Hugh, our drummer, “It sounds great. There’s a great sound on the drums but I can hear a clap just before the backbeat and an ‘ahhhh’ afterwards.” So ‘boom, boom, boom, clap, clap’ became ‘boom, boom, boom, clap, clap, ahhhh!’. I said, “Do you just wanna do that?” [Hugh] said, “No, you do it.” One take and Jeff got fantastic sound. We didn’t think anything more of it, but it became a sort of signature. Because we had a couple of extra tracks to what we were used to, we managed to put down everything that we prepared but then also, any momentary inspiration or an intuitive feeling, we could bung that on as well. There was a freshness because it had to be done so quickly; it often worked and it could be an extra harmony going over the top of something as it was in ‘Changes’ or it could be Chris saying to me, “Why don’t you try a bit of Mellotron on that bit?” And I say, “Yeah, I’m happy to do that.” It was all very quick. Such a satisfying experience.

That was quite funny. The track had been recorded with a guide vocal but Colin was putting the master vocal on. He was getting a bit fed up with it; he was looking at the clock and we’ll come to the end of the session. But I kept saying, “Can you just push that note a little bit or that phrase? It needs to be a bit like this.” And he said, “If you’re so fucking good, you come and it!” And I said, “Colin, come on.” But the whole thing about ‘Time of The Season’, when we did the main track not the lead vocal, we did what we rehearsed and the harmonies that we rehearsed and it sounded great. Jeff Emerick got the most fabulous sound out of the Tom Tom and bass drum; the “boom, boom, boom” and putting a backbeat to the side – “boom, boom, boom, clap, clap” – that was it really but it still sounded good. Then we had half an hour left on the session – and this is a typical thing that happens on ‘Odessey & Oracle’ – I said to Hugh, our drummer, “It sounds great. There’s a great sound on the drums but I can hear a clap just before the backbeat and an ‘ahhhh’ afterwards.” So ‘boom, boom, boom, clap, clap’ became ‘boom, boom, boom, clap, clap, ahhhh!’. I said, “Do you just wanna do that?” [Hugh] said, “No, you do it.” One take and Jeff got fantastic sound. We didn’t think anything more of it, but it became a sort of signature. Because we had a couple of extra tracks to what we were used to, we managed to put down everything that we prepared but then also, any momentary inspiration or an intuitive feeling, we could bung that on as well. There was a freshness because it had to be done so quickly; it often worked and it could be an extra harmony going over the top of something as it was in ‘Changes’ or it could be Chris saying to me, “Why don’t you try a bit of Mellotron on that bit?” And I say, “Yeah, I’m happy to do that.” It was all very quick. Such a satisfying experience.

The current lineup of the band, how does that compare to playing with the original lineup?

They’re different things. But I love the current band: I don’t think the band has ever sounded as good as it does at the moment but then they’re the band I’m on stage with all the time and it just feels very exciting to play with them. I absolutely love where the band is at the moment. I’m not putting down the original band – that had its own character and was great – but I do feel personally that the songs on this album are some of the best songs that I’ve written and some people are reacting beautifully to it saying it’s the best album that we’ve have done since ‘Odessey & Oracle’.

I can hear classic Zombies and bits of ‘Odessey & Oracle’ – was that intentional or did it just come out organically?

It’s never analysed or scrutinised; it’s just really taking an idea and trying to develop it in the way that you naturally feel it. That’s what we’ve always done. In the old days often we didn’t have immediate commercial success because we weren’t copying exactly what was the current hit and record company executives always said to us, ‘what you need to do is something a bit more like this or that.’ We’ve never done that and I couldn’t do that anyway; I wouldn’t want to. You’ve only got one life; you’ve got to try and express yourself. Not everything may come on but when you get to the end of it, you can look back and say, “Well I gave it my best shot.” I think that’s the way to approach everything.

You experimented a bit more on this album with the string arrangements. How complex was the production process with Dale Hanson?

It was very natural. I did the string arrangements myself except for ‘I Want To Fly’, which was done because Chris and I in 1970 produced an album for Colin – a solo album called ‘One Year’ – and that’s the record that he had, ‘Say You Don’t Mind’, with the strings. Chris found this wonderful classical composer who also did a lot of stuff for television and films called Chris Gunning. The marriage of Colin’s voice on that album and some very avant-garde string arrangements was just absolutely lovely. One of the favourite songs I’ve written over the past few years has been ‘I Want To Fly’ and we did record it before on another album. But I said to Colin, “I’d love to look back to the process where we did ‘One Year’” and we had Chris’ arrangement and nothing else from the band, just Chris and [Colin’s] voice. So I played the song to Chris and he loved it. I did the original orchestration on the earlier version that we did of it. Chris said, “Can I hear that?” And I said, “No, because you can’t unhear it. You might hate it or you might love it or anything in between. But I just an honest reaction to the song.” He did it and I absolutely loved what he did and the process of it; that’s why that particular track is on there.

“‘Boom, boom, boom, clap, clap’ became ‘boom, boom, boom, clap, clap, ahhhh!’ We didn’t think anything more of it, but it became a sort of signature.”

Dale put me in touch with Jessica Cox, who was part of The King Strings, which is a String Quartet. I did all the other arrangements but Chris did that one and we recorded them all. I did the Varner version, so the big organ is in a room that has got a very high ceiling – the strings sounded wonderful in there. We recorded them totally in-house. Dale and I had a great working relationship together; we absolutely loved working together. And again, as far as we could make it, the album came out sounding the way we felt the songs and we wanted them to sound; I was absolutely ecstatic about the result. I love working with Dale: he’s just a very talented guy and a lovely person too.

What was the single ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’ about?

It was actually triggered by a real situation. I’m not gonna say what that situation was, but it’s really about when suddenly unexpectedly, emotionally, everything is pulled. The basis of an emotional thing is just borne away without you having any idea why. It leaves you angry: you can’t explain it and you didn’t see it coming. It’s your feelings on that happening. It was a real situation – nothing to do with me I might hasten to add – but I always think that we’re all human beings and we all tend to have similar, major experiences a lot of the time; I love it when people can bring their own towards something so it’s more universal. Bernie Taupin wrote a song for Colin. Colin said, “What’s this song about, Bernie?” He said, “Whatever it means to you.” And then the other one that I remember was Bob Dylan, when someone said, “What’s this song about?” He said, “It’s about three minutes.” I love that because it’s saying ‘bring your own feelings’; if you can relate to the story, bring whatever you want to. If it affects you, that’s wonderful. It was about a particular situation that song, but it was an emotional situation. Someone was being left adrift for no reason that they could fathom.

What were you doing in the desert for five hours when your van broke down on tour in America?

What were you doing in the desert for five hours when your van broke down on tour in America?

We were trying to keep cool! The engine caught fire and for an hour before that there was no air conditioning because first of all it went, and then that caused the fire. We had water thank God, but we were standing outside; it could have been 112 degrees [Fahrenheit]. It was certainly in the hundreds; it might have been 108-110. I’ve been in Phoenix when it was 112 degrees so it could have easily been that. It was just horrendous. But that was the real story of what sometimes being on the road is about: it’s not all glad-rags.

The Zombies’ new studio album, ‘Dropped Reeling & Stupid’, is out now. The band tour the UK throughout April and May.

Photos © as credited or watermarked.

© Ayisha Khan.

KEITH MORRIS & DIMITRI COATS: OFF! – FREE LSD

A decade after their eponymous debut studio album, the hardcore punk supergroup release their new record, ‘Free LSD’, with a fresh direction and lineup change that takes them beyond their stereotypical black-and-white image. As well as seeing Raymond Pettibon’s artwork released on a coloured sleeve for the first time, the album deals with serious sci-fi subject matter like UFOs and conspiracies – drawing from Keith’s podcast on the subject – spewed through the spectrum of more expansive influences via noise feedback, electronics and metalhead rhythms to refresh their canvas. The album is also accompanied by an upcoming sci-fi feature film, written and directed by the band and premiered at this year’s Slamdance film festival. Before their London show on their European tour, I spoke to band founders, frontman Keith Morris and guitarist Dimitri Coats, about making their new album and film, covering a Metallica song for Metallica, cosmic influences and close encounters of the third (or fifth) kind – both human and alien – and how Keith doesn’t want to be the ‘nervous breakdown’ guy anymore.

How does this album differ to your previous releases?

D: We weren’t trying to communicate with extraterrestrial life prior to this album. We took a note from Sun Ra: we put our antenna out to the cosmos and we were very open to receiving music from an intergalactic source.

K: Dude you are such a fucking liar! We were trapped in a submarine under the polar ice cap and there was nowhere to go. We consciously made an effort; we looked at each other and thought, “Hey! Let’s try something new.” If you’ve noticed our album covers, the first three are black and white. That gets boring after a while. If you look at the new album cover, the unidentified flying object is passing off all of these different coloured lines or the different coloured lights in the sky. We love Stiff Little Fingers, we love The Damned, we love The Ramones, we love Black Flag…I kind of love the Circle Jerks. It was time to go someplace else. Can we? We know that we have roots amongst all of this and we normally have certain records that we go to for inspiration. This time around it was like, “Let’s listen to some different stuff.” [Dimitri’s] a closet industrial noise freak.

D: I’ve come out of the closet. I’m really excited because I’m gonna get a tour: right around [Hackney] is where Throbbing Gristle used to live. I’m excited for my friend to show me the history around here.

K: What you need to do, because he’s wearing a Bastard Noise T-shirt, is ask him what his favourite Bastard Noise song is. You see these kids wearing a Motörhead T-shirt or a Black Sabbath T-shirt or a Dead Kennedys T-shirt and they’ve never even listed to the music so he could be pulling your leg. But actually he had me listening to this stuff. I know about these bands and I have some of their records in my record library, but they’re not records that I zoom in on – it’s a special taste. You don’t eat McDonalds three times a day: you only eat McDonalds once a day. You have two other meals, so make it interesting. We went to outer space with Sun Ra; in the process our drummer [Justin Brown] had played with Herbie Hancock and I had witnessed Miles Davis play with Herbie Hancock in The Headhunters backing him in his band. Being a punk rock guy, a heavy metal guy and a hard rock guy, why do [I] listen to Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis? Well, maybe because they’re frontline jazz musicians.

K: What you need to do, because he’s wearing a Bastard Noise T-shirt, is ask him what his favourite Bastard Noise song is. You see these kids wearing a Motörhead T-shirt or a Black Sabbath T-shirt or a Dead Kennedys T-shirt and they’ve never even listed to the music so he could be pulling your leg. But actually he had me listening to this stuff. I know about these bands and I have some of their records in my record library, but they’re not records that I zoom in on – it’s a special taste. You don’t eat McDonalds three times a day: you only eat McDonalds once a day. You have two other meals, so make it interesting. We went to outer space with Sun Ra; in the process our drummer [Justin Brown] had played with Herbie Hancock and I had witnessed Miles Davis play with Herbie Hancock in The Headhunters backing him in his band. Being a punk rock guy, a heavy metal guy and a hard rock guy, why do [I] listen to Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis? Well, maybe because they’re frontline jazz musicians.

You used to have a jazz drummer in Circle Jerks?

K: Yeah, that would be Lucky. We don’t talk about Lucky because [he’s] on television and a multimillionaire; his ego trip far surpasses his talents.

D: Ooh. Ouch.

K: No, it’s the truth. Zander [Schloss] and Greg [Hetson] played with him in his home studio and were horrified.

Why did you do a cover of Metallica’s ‘Holier Than Thou’?

K: They came to us and asked us to perform a song for their ‘The Black Album’ tribute – it was a big fundraiser. I listened to the album: their biggest hits are on that record, like ‘Enter Sandman’ and a lot of stuff that was on the radio. That’s not where I want to hear Metallica; I don’t want to hear those songs. I want to hear stuff off of ‘Ride The Lightning’ and ‘Kill ‘Em All’ and ‘Master of Puppets’ – that’s the Metallica that I know. But they asked us to perform a track so we listened to the album. And Autry [Fulbright], Dimitri and I, all three of us, zoomed in on one song and that was ‘Holier Than Thou’. So it was unanimous that we were going to cover this. We didn’t have a drummer at the time and it made perfect sense: let’s use Justin, who Autry worked with in Thundercat. Autry said I’ll ask Justin if he wants to play with us and we recorded the track. All of the guys in Metallica were beyond stoked. They were excited like, “This is really cool. Thank you guys.”

What about the religious theme in the video?

D: Autry had the idea of us being the church band that mistakenly got booked. Then our director Chris Grismer took that idea and developed it. It really is the song that brought the band together.

K: If you listen to the lyrics it’s basically, “Hey, don’t bog me down in your religious garbage. You know I got stuff to do; I’m a good human being and I don’t need to get caught up in all of that.”

D: And all you altar boys better be real careful in those Catholic churches!

K: If you watch the video, we were very fortunate: some of the actors and actresses that showed up to be in the video are also in our new movie.

How did the film come about and the theme with the psychedelic drugs and sci-fi?

D: I was growing tired of the black-and-white punk rock world that Keith described earlier where I would try to write certain riffs and he would start yelling at me, “We can’t do that. We don’t do that in this genre. You can only play like this. This is our target: we have to head for the bullseye.” [It] just felt so restrictive. I fooled Keith into experimenting and thinking outside the box by convincing him that our next record should be a soundtrack for this crazy sci-fi film that I wanted to make. Then he just took the ball and ran with it, especially when we drew inspiration from a podcast that he has in real life called ‘Blowmind Show’, in which he touches on a lot of things that are alternative media. It’s heavy into the idea that aliens and UFOs exist and so we had fun with that topic. What it allowed us to do is every time we hit a creative fork in the road, if we would normally go right, we would go left. Starting with how I tune my guitars, to the lyrical subject matter to the artwork being colour for the first time…everything was a conscious decision to push our creativity into a new direction. Because, much like The Beatles with Sgt. Pepper thinking, ‘Let’s filter our songwriting through these other people. We won’t be the Beatles anymore. We’ll be Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,’ it did wonders. So we were really fortunate in that our psychedelic window that we were looking through took us into a completely new territory.

Drugs can be a major part of the creative process, what’s your personal experience of this?

D: I’m a big fan of marijuana. I could not have been more high when I wrote the music for this album. And I could not have been more high when I wrote the script for the movie, with headphones on listening to noise, experimental music, post-industrial…whatever you want to call it. I just went into another world. Yeah, it’s always been a creative friend. It’s really the only drug that I allow myself because I find that if I start dabbling in other things, I start making bad decisions and I don’t associate weed with anything else. I don’t get stoned and suddenly think, “Let’s get a bag of coke. Where’s the party?” It’s a sacred herb to me.

So what about in the film?

D: It’s not a drug at all – it’s an antidote. The music is the drug. The antidote holds the key to an alternate dimension in which the band exists. The film takes place between two different realities: one where we are ‘off’ and one where we are not necessarily musicians and we certainly don’t know each other. Our music holds the key to an awakening of human consciousness. There are two rival alien species: one which desperately needs us to make the album and one which is trying to prevent us from making the album.

K: And it’s a love story.

Can you talk about some of the album tracks and how those relate to scenes in the film?

D: There’s a whole bunch of songs from the album that are featured in the film, some of which we perform; others that just create a score for the action that’s taking place. Certain characters have lines in the film that are lyrics from the record. They are completely joined, but the songs don’t necessarily point directly to the movie and the movie doesn’t necessarily point directly to the album. Although the album is featured in the film; literally, it does hold the key to releasing the human species from the clutches of this evil alien race, which is kind of like the all controlling Illuminati.

With your lyrics, Keith, how did they relate to real life?

K: When we first started working on the album, Dimitri asked me, “What are you gonna sing about?” I was a bit stumped. He said, “Because you’re always singing about politics; you’re always singing about social climate situations. A great place for you to start is a place that you’re going to be able to get the majority of your lyrics. You’ve already written a ton of lyrics – they’re buried in your podcast. So you need to go back and listen to episodes of your podcast. You need to go and pull the most important episodes.” That’s what turned into the lyrical content. We got into some documentaries; we went deep: a lot of these conspiracy theorists, they’ll go to Google and look at the very first thing when they type in whatever conspiracy they’re concerned with, they’re thinking about or delving into, and they’re not really delving into it, they’re not really going past the first couple of posts; they need to go deeper into it. One of my best friends, Pete Weiss, and [I] have a podcast called ‘Blowmind Show’ with Pete and Keith. All we did was talk all of these different conspiracies. Do UFOs exist? Does Bigfoot exist and who killed JFK? And what about the missing 411? Why are they finding these naked kids sitting on rocks with all of their clothes perfectly folded next to them out on a mountain range; how did they get there? All sorts of really oddball stuff; we went deep and discovered some of the stuff that was going on outside of Las Vegas in Nevada and went to a place called the Archer Farms La Mesa which is a big, big military, industrial complex.

K: When we first started working on the album, Dimitri asked me, “What are you gonna sing about?” I was a bit stumped. He said, “Because you’re always singing about politics; you’re always singing about social climate situations. A great place for you to start is a place that you’re going to be able to get the majority of your lyrics. You’ve already written a ton of lyrics – they’re buried in your podcast. So you need to go back and listen to episodes of your podcast. You need to go and pull the most important episodes.” That’s what turned into the lyrical content. We got into some documentaries; we went deep: a lot of these conspiracy theorists, they’ll go to Google and look at the very first thing when they type in whatever conspiracy they’re concerned with, they’re thinking about or delving into, and they’re not really delving into it, they’re not really going past the first couple of posts; they need to go deeper into it. One of my best friends, Pete Weiss, and [I] have a podcast called ‘Blowmind Show’ with Pete and Keith. All we did was talk all of these different conspiracies. Do UFOs exist? Does Bigfoot exist and who killed JFK? And what about the missing 411? Why are they finding these naked kids sitting on rocks with all of their clothes perfectly folded next to them out on a mountain range; how did they get there? All sorts of really oddball stuff; we went deep and discovered some of the stuff that was going on outside of Las Vegas in Nevada and went to a place called the Archer Farms La Mesa which is a big, big military, industrial complex.

D: Watch this [shows video of a UFO]! This is my house. Look at this fucking thing! Look at that, that’s not a star; look at it move in my backyard [in Claremont, California]. There’s this one documentary that we were very inspired by called ‘Unacknowledged’. The follow up to ‘Unacknowledged’ is ‘Close Encounters of The Fifth Kind’ of Dr. Steven Greer. It’s all about being open to this idea that aliens exist and inviting them in and, when you do that, you’ll start to have these experiences. While we were working on all this stuff, I started to really become more tuned into what was happening; I started to have some of these encounters and that’s from that time and I saw other things. It’s another reason we love this project so much. There is comedy to what we do but there’s also legitimate passion behind why we went into that direction and we believe…

K: ….very seriously.

“Our music holds the key to an awakening of human consciousness. There are two rival alien species: one which desperately needs us to make the album and one which is trying to prevent us from making the album.”

How did you enjoy doing the acting and directing?

D: I’ve had some acting experience, which is why I felt comfortable directing, but there were a bunch of non-actors that we pulled in from our music world and beyond. Keith is the lead in the film and there were people who pulled me aside and said, “Hey, are you sure you know what you’re doing? He’s never acted before, you have him as the lead role in your movie.” It’s a gruelling experience to make a film: sometimes you’re up all night and then all of a sudden you have to switch gears and you’re filming in the daytime. I just had this feeling [Keith’s] gonna shine and he really did – he’s fucking awesome in this film.

K: It still doesn’t mean that I’m your friend because you’re saying these nice things about me. In the beginning, [we] threw ideas around as to, “Have you seen ‘The Monkees’ Head’? Have you seen Frank Zappa’s ‘200 Motels’? Have you seen any of these movies involving other rockstars or rock musicians?” Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’. Of course, there’s the two [The] Who concept movies: ‘Tommy’ and ‘Quadrophenia’. All of these movies: they’re all fun; some of them are very serious. Some of them have extremely talented and established actors. We didn’t: our things a lot of fun. It’s ridiculous. One of my mantras, one of my thoughts towards what we were doing is ultimately when we show the movie, I want to be able to see people talking amongst themselves as they’re leaving the building. I want to see somebody scratching their head going. “What the fuck? Who allowed these guys to make this movie? What did I just see? What did we just watch?” Just as serious as it is, it’s also very playful. Some of it’s very heavy handed and some of it’s very light-hearted. It goes in a lot of directions.

Can you tell me about your label Fat Possum records?

D: Great label. Who wouldn’t want to be on a label that has everything from Royal Trucks to Townes Van Zandt…and Al Green.

D: Great label. Who wouldn’t want to be on a label that has everything from Royal Trucks to Townes Van Zandt…and Al Green.

K: Don’t forget they’re based in Mississippi and their whole foundation of that record label was all of the guys that nobody wanted and had never got a D-model Ford. Who’s the guy that’s missing a couple of fingers? He plays with a Ford knife. He’s really great. But there’s so many.

D: We’re label mates with Spiritualized; it’s a really eclectic roster.

K: We’re label mates with Iggy Pop.

D: That’s something we were looking for because we knew that this album was us stepping outside of the punk rock genre and we wanted to be taken seriously as a band that can do something. Like having a drummer who plays with Thundercat and toured with Herbie Hancock coming in: taking what was already really adventurous material that we had written and elevating it to this other place, doing things that no rock drummer would ever think to do. It’s a big reason why the sound is so adventurous. We played into that: we created these four interludes ‘F’, ‘L’, ‘S’, ‘D’ that are free jazz, punk noise. We have John Wall from Clay Hammer on saxophone. We’re really trying to expand.

I’ve always felt like OFF! was a quickfire challenge in terms of where I came from versus what I was allowed to do. If I was used to painting with oil paints, it was like somebody coming along and going, “Here’s a sheet of paper and a Sharpie. That’s all you get.” Okay, you can make good art like that, but now we get to re-approach what we do with all the paints at our disposal; anything we wanna try or use. It’s creatively a triumph for the kind of band that we are.

You had a lineup change in 2021 with the departure of Steven Shane McDonald and Mario Rubalcaba. How did that come about and bring new life to the band?

D: Everybody’s gone on to do other things. It’s not like we wanted the original lineup to fall apart: we tried for a couple of years to do what we’re doing now with them. But we were just stalled out on the side of the road with a flat tyre and no one was helping us, and it became very clear that their priorities were not in line with where we needed to go. We had to make a change in order to survive and move forward – it’s as simple as that. We don’t have any hard feelings towards them. Sometimes things happen for a reason and I really, really believe that this album and all that we have going on right now would not be quite as special if it weren’t with Autry and Justin. They breathed new life into us and helped us reinvent ourselves.

K: We hit a wall. We were more than accommodating. One of the reasons it took so long for us to get to where we are was because we kept stumbling and fumbling over the hurdles. Dimitri rewrote the script to the movie probably a minimum 12 times – it could have been even more – because we went through four different lineup changes. Mario saying, ‘I can’t do this because I’m not an actor.’ So we get Dale Crover from the Melvins and he’s a great drummer. We record with Dale; we’ve recorded like 23 songs with [him] and the majority of them were pretty happening. Some of them we would have had to have gone back and re-recorded. But then Mario hears what we’re doing and it’s like, ‘Oh, no. I‘ve got to be a part of this because you guys have come up with stuff; nobody else is doing anything like this.’ So now [Dimitri’s] got to rewrite the script including Mario, who was in the original script but said [he] can’t act – it just kept going back and forth.

We actually took our time working on the material for the album to allow the two original members of the band to go out and play with all of their other bands; we were more than accommodating. It was like, “Please go out and do what you need to do. You’ve got kids, families, wives, dogs and houses and you got to pay your bills.” We don’t have any money: Dimitri and I are eating soup. Our ‘Per Diem’ was a meal a day and we purposely set out on this path to allow those guys to go out and do what they needed to do and get it out of their systems so at the end of the two years, it would be our turn: “Guys, this is what we’re doing. Guys, we want your full attention on this.” And we couldn’t get it because they were still playing shows. We wanted two months in the studio to be able to record all of this different stuff and be creative as a band, rather than just Dimitri and I having written all of the songs. There was gonna be more to this; there was gonna be more creativity and it didn’t happen. It was like, ‘I can’t be in the studio today. Because I’ve got PTA; I can’t be in the studio today because I’ve gotta take my son to school and I gotta pick him up at the end of the day; I can’t be in the studio today because my wife’s tonsils need to be removed,’ or whatever. Whatever the excuses; all of a sudden there were more excuses happening.

“We were just stalled out on the side of the road with a flat tyre and no one was helping us…we had to make a change in order to survive and move forward – it’s as simple as that.”

D: There was an actual excuse, “It’s my dog’s birthday.” Do you remember that one?

K: That would have been the same kind of an excuse that Greg Hetson would have used. Remember all of those excuses that he pulled up? “I ordered a brand new computer, it’s sitting in the post office in Long Beach and they’re the most corrupt post office in the world because all the people that work there steal everything out of the back.’ “Okay, go get your computer.”

D: Anybody who’s ever been in a band, no matter how successful or how good or bad it was, knows how difficult it is to keep a band together, even under the best circumstances. That’s my friend Kevin right there [points]. He was in a band called Dandelion with his brother – these are brothers. Now you would think brothers can work it out but we know because of The Kinks, Oasis and Black Rose, that it’s fucking impossible. So even best of friends…we’re best of friends and dude, I could tell you stories of [Keith]: we’re trying to work on a song and he stands up and throws a fucking drink across the room and storms out. I wasn’t that worried about it. He came back and we continued working on the song – it ended up being a good tune.

K: We hit a lot of bumps in the road and, like I’ve said, we were more than accommodating. We were expecting something that was not going to happen and, at a certain point, Dimitri looked at me and said, “I’m not doing this anymore. I don’t want to be in a band with guys that don’t want to participate and be a part of it.” I had to do something that I did not wanna do; I’m still hurt from it and I will hurt from it for a while because he was like my younger brother, but it had to be done in order to save the band.

D: Also I’m gonna say something very important, which is Keith is a living legend, but with that comes this sort of…

K: Garbage.

D:…pressure of being this certain person. He’s always got to be the nervous breakdown guy. People are more than one thing – he doesn’t even really listen to punk rock. If you go to his house, he’s playing all kinds of fucking music, everything from Ornette Coleman to Ravi Shankar…you name it. He’s a real fan and very knowledgeable person when it comes to pop culture and art. I know from being his friend that he’s always wanted to do more than just be Keith Morris from Black Flag and Circle Jerks and yet there’s this pressure. One of the biggest accomplishments of this project is we’ve been able to shine a different light on that and I think it’s his finest moment. I think a lot of people would agree with me and that’s saying a lot because he’s done some fucking amazing shit in the past.

“Keith is a living legend, but with that comes this sort of pressure…he’s always got to be the nervous breakdown guy. People are more than one thing – he doesn’t even really listen to punk rock.”

And the anger is still there…

K: There’s too much stuff to be angry about; if you’re not angry about some of the shit that’s happening in the world, you don’t fucking live in the world. All we want to do is just be good people. We want to be able to walk our streets, enjoy our friendships, have a good time and we don’t want to be fucked with. It’s like every time you turn around, you’re getting fucked with. Our governments – the British government and the government of the United States of America – and all of the politicians…there’s probably six politicians between both countries that should live and be able to say the things that they do and all the rest of them should be fucking shot and dumped into the oceans. We could chop them up and use them as shark bait.

OFF’s new studio album, ‘Free LSD’, is out now. Their Record Store Day release, ‘FLSD EP’, is out on April 22.

Photos © Anna Marchesani/Nocturna Photography.

© Ayisha Khan.

BRIX SMITH – VALLEY GIRL

Following the dissolution of her last band The Extricated, the former Fall guitarist and songwriter releases her long awaited debut solo album, ‘Valley of The Dolls’, with a fresh, all-female touring band to accompany it. Ahead of its release, Brix Smith excitedly spoke to me about her struggles to get the finished product out amongst lockdown and Brexit chaos: from her spiritual amalgamation with producer Martin ‘Youth’ Glover who helped her find her feet, her coming-of-age journey spanning her exhilarating but often isolating Manchester days, her collaborative songwriting to fully fledged solo artist and her personal experiences along the way, from a childhood growing up in the California Valley, a recent health scare and finally owning her feminist punk rock attitude.

Why has it taken you so long to release your debut solo album?

The original idea to release it was back in 1982. When I first started writing songs, I was about 17/18 years old. I was excited when I formed a band and everyone in school was like, “What are you doing in school? You’re such a good songwriter. Just go out and do it for real.” So I took a term off, went to play in Chicago with my bandmate Lisa; [I] famously met Mark Smith, who heard those songs that I’d been writing, wanted me to come to England so that he could produce me and buy me a record deal, and I would do a solo album. But they ended up using those songs for The Fall and I joined. [The album] should have been all that time ago. Of course, it’s not the same songs anymore and a lifetime has passed, because I was so young, I was too insecure to stand up under my own name, so I put it under the guise of another band. It was kind of cool to be secret.

I did The Fall famously for a couple of stints, then played with lots of different people and for The Extricated a few years ago with some of the ex-members of The Fall, which I fully enjoyed doing – it really got me back in the saddle. But again, although it was my name in the title, it wasn’t me making the decisions. I was writing all the lyrics and all the melodies, but it was collaborative, as The Fall was as well. Before lockdown came, Nadine Shah, a really good friend of mine, just sat me down one day and, in her own brutal way, said you need to be celebrated for you. “This is not really working for you. I think you need a proper manager. I think you need a whole new team around you.” She said, “You’re fucking Brix Smith.” I started crying: although it was a little bit upsetting to hear and I was having a great time with The Extricated, I knew that she was right. And I knew that the time was now.

So she put me together with her manager, who also managed Youth, and suggested, “Why don’t you write with Youth for other people, just see what happens? It’s all about the music at the end of the day.” At this point, I just thought of myself as a songwriter. I could do lots of things but songwriting is a really important and interesting craft, which I have honed my whole life. I’ve been writing, lyrics and poetry, since a child and music. So Youth and I were meant to get together but then lockdown happened. We couldn’t meet: he was in Spain and I was here; we were stuck apart. The Extricated naturally evaporated: everyone was in Manchester and couldn’t carry on. Some of them have young families; everything was fucked up. So Youth and I had a discussion on FaceTime – we’ve never met in real life after all those years of being in bands that were just crossing paths. We talked about what music I loved, what were my early inspirations and had some fucking deep magical connection from the beginning. He sent me some backing tracks he thought might be right, and they were…my mind flew, and I taught myself how to record at home, set up a studio during lockdown, engineered my vocals, wrote the thing and we started to swap files back and forth.

“She said, “You’re fucking Brix Smith.” I started crying: although it was a little bit upsetting to hear and I was having a great time with The Extricated, I knew that she was right.”

After about the first or second song he just said, “Oh my God! This is amazing; this needs to be your solo album. You need to do this – this is your Marianne Faithful broken English moment. This is this is your moment.” I just needed to be completely competent, comfortable, fully, fully own my power and talent and stand up there and actually not give a fuck what anyone else thought; make the music that was literally the music I always wanted to make without anybody else having an input. Youth and I played everything on the whole thing; it’s just me and him, except there’s a drummer who did the drums. But really it’s just Youth and I so it’s a solo album. When I go on tour now with my girls – like Deb Goodge from My Bloody Valentine – they’re my touring band. I’m not sure what’s gonna happen in the future when I start writing again; probably because I love playing with them so much they’ll be on the next one, but it will still be under my name.

The reason my album took so long to get out was because, during lockdown, so many people were supposed to have albums out and they couldn’t tour, so they backlogged, backlogged and then when touring started everyone started to release at once; mine was pretty much ready but not 100%. Look, there’s no pressure: I don’t have a record deal yet, whenever it comes out, it’ll be the right moment; the universal will see to it blah, blah, blah. I had to get everything going in terms of building the team of people around me that I really loved, trusted and have fun working with. Never again am I going to work with people that are horrendously challenging. It’s just got to be a great flow, otherwise what’s the point? Then there was a backlog from Brexit: we could not get any cardboard to print the sleeves. And there was a backlog at the pressing plant of six months, because everyone needed to get their records pressed and cut, and there’s only so many places now in the UK and Europe that do it – it’s a dying art. So it just got put back, put back and then another bout of covid…it took ages.

Are you Brix Smith now as opposed to Brix Smith-Start?

I’ve always been Brix Smith. Smith is my last name on my passport; Start is my married name and I used that for a while, although I’ve never changed it so it’s not my legal name. When Phillip [Start] and I opened the shop, I had a breakdown and stopped writing music for 15 years because I just felt so brutalised and kicked to the curb. There was a very dark patch in my life where, after the second stint in The Fall, I broke apart and I needed to pivot, so I started doing fashion which is a passion for me and a skill set that I didn’t realise I had, but I loved it. Philip and I started these shops called ‘Start’, which was his last name, so I became Brix Smith-Start to associate myself with the fashion work. When I went back into music again my manager said, “Just go back to Brix Smith. Everyone knows you as that; Brix Smith-Start is a mouthful.” It isn’t even my legal name, although I’m still happily married to Philip Start. So I am Brix Smith – that is who I am.

I’ve always been Brix Smith. Smith is my last name on my passport; Start is my married name and I used that for a while, although I’ve never changed it so it’s not my legal name. When Phillip [Start] and I opened the shop, I had a breakdown and stopped writing music for 15 years because I just felt so brutalised and kicked to the curb. There was a very dark patch in my life where, after the second stint in The Fall, I broke apart and I needed to pivot, so I started doing fashion which is a passion for me and a skill set that I didn’t realise I had, but I loved it. Philip and I started these shops called ‘Start’, which was his last name, so I became Brix Smith-Start to associate myself with the fashion work. When I went back into music again my manager said, “Just go back to Brix Smith. Everyone knows you as that; Brix Smith-Start is a mouthful.” It isn’t even my legal name, although I’m still happily married to Philip Start. So I am Brix Smith – that is who I am.

How did your collaboration with Marty Willson-Piper lead to you finding your place with this album?

That was written in the early ‘90s; from ‘92 to ‘95. I was living in LA, in between my stints in The Fall. A really famous agent had put us together [for me] to write as a writer because that’s how I always have it; I made this album with Marty. It was really beautiful and lovely and very much me and very much him too; it was a duo album. When I came back here, rejoined The Fall, finished up that album in Cornwall and went to get a deal with [it], nobody would answer the phone. It was mid to late ’90s, I was already in my 30s – over the hill for them. It was a time of All Saints. I don’t even think people listened to that album, so it broke my heart because it was such a beautiful album. I really believed in it, I worked so hard on it and I put so much emotional content into it. I was devastated and that is what made me quit the music business.

[Later on] I got a new manager through Youth who heard what we were working on, called Nick Lawrence. He said to me, “Do you have anything that’s never been released? I’d like to start assembling a body of work for you. I like to make you a proper website. Let’s get a full cannon of your work.” And I said, “Well actually, I do have this album.” At the time it wasn’t called ‘Lost Angeles’ (I call it that because it was the lost years between The Fall). I have to dig back to get the DHTs by the guy that produced it. I haven’t listened to it for 15 years. I had such a devastating experience with being kicked to the curb which I didn’t realise wasn’t about the album: it was about people just not being open to listen to it – no one cared. It wasn’t like no one listened to it and said this was shit; they just didn’t listen. I took it personally but it wasn’t. Anyway, I found it, tracked it down and sent it to Nick and said, “I’m just gonna push the button. I can’t promise it’s anything.” He immediately came in and goes, “Oh my god! This is a beautiful album, You’ve got to put this out.” So that’s why it came out, however many years later.

How did you bring your personal experience into that album, laying bare your experiences in your work?

I’m laying it bare because I’m the same as everybody else. We’ve all been through so much in whatever capacity. Obviously I’m speaking from my own experiences, but I’m really hoping that my experiences are going to resonate heavily with everybody that has been marginalised, kicked to the curb, told they’re not good enough; underestimated, undervalued for whatever reason. It’s time for me to fucking grow a pair, stand up and speak for those that I can help. I’m comfortable talking about anything: I don’t have a filter, why should I? We’re all vulnerable human beings.

With the ‘Lost Angeles’ album, that was a time when I was very raw from my separation/divorce from Mark Smith and Nigel Kennedy and I’d been through the mill. I also had a very challenging and crazy boyfriend during that time in LA; a well-known record producer who was very misogynistic. I was trying to find myself as woman – as a human – and not attach myself to another man; I was processing what it feels like to be in really intense relationships and then being on your own. A song like ‘Little Wounds’, for instance, I originally started thinking about when you look at dolphins or sharks in the water – their bodies are covered in little scars. Every little scar tells a story: what bit of coral they got scratched on or what fish fight. And I thought, actually we all have little wounds; all of us. Some you can see and some you can’t, but those are the things that make us stronger. Although they initially hurt, they heal and you go on and learn from them. It was stuff like that.

With the ‘Lost Angeles’ album, that was a time when I was very raw from my separation/divorce from Mark Smith and Nigel Kennedy and I’d been through the mill. I also had a very challenging and crazy boyfriend during that time in LA; a well-known record producer who was very misogynistic. I was trying to find myself as woman – as a human – and not attach myself to another man; I was processing what it feels like to be in really intense relationships and then being on your own. A song like ‘Little Wounds’, for instance, I originally started thinking about when you look at dolphins or sharks in the water – their bodies are covered in little scars. Every little scar tells a story: what bit of coral they got scratched on or what fish fight. And I thought, actually we all have little wounds; all of us. Some you can see and some you can’t, but those are the things that make us stronger. Although they initially hurt, they heal and you go on and learn from them. It was stuff like that.

What is ‘Living Thru My Despair’ about personally, was it about Mark Smith/The Fall?

It’s interesting you ask about that because I ummed and arred about putting that as the first track: it was quite a statement. Mark [Smith] famously wrote many, many songs about me after we broke up – even when I was still in the band – and I wrote songs about him because there was unresolved stuff, during The Extricated for instance. Not just about him; I had an unresolved stuff within me, not really anything to do with him. I blame no one for any choice I made in my life. ‘Living Thru My Despair’ – yes, there are a lot of Manchester references in it. I was very lonely when I lived in Manchester: I didn’t have any girlfriends. I was completely immersed in The Fall, but I was also a fish out of water. I moved to a different country, a different city and a very different way of life than I was used to and there was a lot going on. So I wanted to paint a picture, but the positive is you go through hard times and you live through [them]. Not all that was bad either. It’s a song about strength; all of these songs are about finding your strength and your power through pain and adverse situations or situations where you have to galvanise yourself. Manchester was hard but it’s not particularly about that. I always say my heart is half-Mancunian and so I love it too.

Does the album name have anything to do with the film ‘Valley of The Dolls’? ‘Dolls’ being a slang word for drugs…