SHAUN RYDER @ THE WATER RATS, LONDON

Happy Mondays frontman Shaun Ryder did an intimate Q&A in which he had “more stories than a fucking library”, touching on his early life growing up in Salford, musical influences and time in the Madchester indie dance rock group, which saw him work with legendary producers such as John Cale, Martin Hannett and DJ Paul Oakenfold overseeing the creation of the band’s best known albums ‘Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile’, ‘Pills ‘N’ Thrills And Bellaches’ and ‘Bummed’.

Happy Mondays frontman Shaun Ryder did an intimate Q&A in which he had “more stories than a fucking library”, touching on his early life growing up in Salford, musical influences and time in the Madchester indie dance rock group, which saw him work with legendary producers such as John Cale, Martin Hannett and DJ Paul Oakenfold overseeing the creation of the band’s best known albums ‘Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile’, ‘Pills ‘N’ Thrills And Bellaches’ and ‘Bummed’.

Ryder grew up in a home where from the age of three he was listening to The Beatles, Elton John, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones and “all sorts of hippie music”; his first gigs were seeing the Buzzcocks and The Ramones and David Essex was his inspiration to be in a band: “[David Essex] became a rockstar and died of a heroin overdose in a big castle in Spain and I thought I’m having that, but I’m not dying of a heroin overdose!”

He also provided an insight into the famed ‘Madchester’ scene of the late ’80s: “‘Bummed’ was when things started changing; all the ecstasy was there – we checked into a studio and went mad for about three months. And [Martin Hannett] the producer was fucking more nuttier than us lot. We were just doing what we did which was rubbing off everything: funk, Northern Soul, punk rock, the lot…and then that drug came in and it changed everyone’s way of doing things – everyone got funky.”

Ryder spoke a lot of about Happy Mondays’ drug use and their open approach to the subject compared to other bands of the time and how it was the key to their commercial success: “We were on a fucking half-arsed label and we just said what we wanted to say. Piers [Morgan] put us on the front of The Sun with Ronnie Biggs and then we sold 300,000 fucking records. In the late ’80s we went back to how it was in the first Summer of Love, ’cause we were just an honest fucking bunch of kids who didn’t have anything to be embarassed about. We were just doing drugs.

“You’re gonna meet the NME in a pub but you’d walk in, chuck a line out on the fucking pool table and the next thing you’ve got the centre pages. We wasn’t the best writers ’cause we was learning to write; we wasn’t the best musicians, we were still learning to play; we couldn’t produce ’cause we didn’t know a fucking thing about being in the studio, so you use what you’ve got and that’s what we did.”

He later talked about how the Mondays came to an end on the recording of ‘Yes Please!’, paving the way for his new venture, dance funk duo Black Grape, which he said is currently recording a new studio album.

21/02/20: Shaun Ryder @ The Water Rats, London.

Photos © E. Gabriel Edvy/Blackswitch Labs.

© Ayisha Khan.

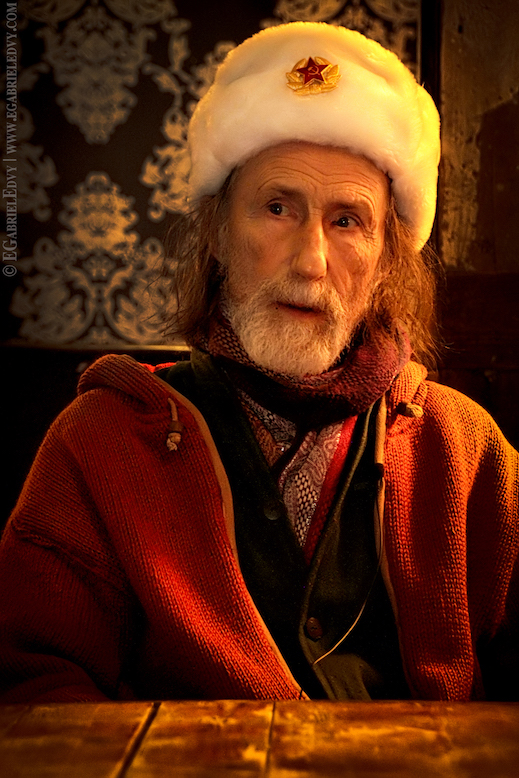

ARTHUR BROWN – THE GOD OF HELLFIRE

Arthur Brown, at the grand age of 77, is the poetic embodiment of the spiritual awakening that he names the ‘god of hellfire’. From his upbringing in the Blitz, fire has always been both a nightmare vision as well as an enthralling fascination, which later led to the creation of his 1968 debut album ‘The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown’ and his UK number one single ‘Fire’, which sold a million copies nationwide and awarded him a gold disc. But beneath the surface of his early commercial success, Brown concerns himself with the next stage of his inner spiritual journey, from his days growing up in a world of ’60s psychedelia and radical thinking. bold experimentation with visuals and magic and the relationship with his fans, utilising electrifying theatrical performances to provide holistic sustenance to both his and their awakening state of consciousness. Brown talks to me ahead of two consecutive London shows symbolising ‘perspectives of the human adventure’ and a significant culmination in his career.

What are these shows about?

The guy who first created a website for me a long time ago was at our show last night. He said, “All the things you wanted to put into the show with [my] band between ’72 and ’75 but couldn’t because of the technology of the day, you’ve done it now.” We’ve created a multimedia show that has very exciting music and very unusual ways of using visuals. It has different depths depending on what you want to look at it. It’s a movement through, which would normally be a story. Claire and I (Claire is my manager, she also does the costumes and theatre) have Andy on the visuals who can in real-time play with images and make them mirror whatever we’re doing and create these depths. Tonight we won’t be able to use all the depths, but we will use some. These are screens here, so you get the double level of projections. It’s taken Claire and I about four years to understand what I like to talk about, think about and what the material I write is about, and get to a point that the material we use is different material from different times in my career, by knowing the whole background, what concerns me; what’s in my heart.

Your latest album, ‘Gypsy Voodoo’, how does it symbolise what stage you are at in your musical and spiritual journey?

Well it’s relevant in this act that we have…the silence and the place where there’s not physical bodies moving or things from everyday life. That’s the place it all rocks around and that’s like a mirror to consciousness and thought.

You had two (remastered) tracks on there, ‘Fire’ and ‘Fire Poem’ – what part does fire play in your music?

I was born in the war in Yorkshire and then when we moved to London, the East End, in the Blitz, both these places where our houses were were blown to bits and all the streets were in flames, so fire became a preoccupation. Also there was no television and people were poorer after the war – even people who before had huge houses – so I found a great deal of pleasure watching fires, flames in the house and how they come out a certain colour, they flicker up and then greens and blues come out. And then as it gets hotter and hotter there’s all this movement because whatever is burning falls, so everything shifts in fire but then it gets to a point where the centre of it is white hot and that doesn’t move; everything is suddenly silent. So for me the flames and the fire represent the kind of movement through your own mind and all that preoccupies and bothers you.

Also the dualities of fire, how did that play a part in you being the ‘god of hellfire’?

The original album was a story although it wasn’t in prose; it was a poetry sequence and in it this person looks at the world, sees it as quite nightmarish and a voice says from inside, “There’s only one way out: you have to bathe yourself in fire.” So that’s what the lead character does and then meets these gods, and one of the gods is the god of hellfire. If you shifted away from the centre of your consciousness, which allows you to behave in a humane, harmonious fashion, if you wanna get back to that you have to somehow work through and that’s the god of hellfire; that’s what the god of hellfire is. It’s kind of purgatory in Christian terms or even some of the other religions. And then comes in the next figure, his god brother. It’s not like that. Fire is also aweing. This is the god of pure fire who says, “When you see a fire burning inside your mind’s eye, breathe the meaning of the flames before you let them die.” And then it says, “Twisting, turning, falling, burning, roaring balls of fire; those who see them have no need of guides to spend awhire.” If you can see that and hold it you don’t need gurus and teachers, but [for] most people it’s too difficult; our education doesn’t deal with it, although it’s quite natural.

The original album was a story although it wasn’t in prose; it was a poetry sequence and in it this person looks at the world, sees it as quite nightmarish and a voice says from inside, “There’s only one way out: you have to bathe yourself in fire.” So that’s what the lead character does and then meets these gods, and one of the gods is the god of hellfire. If you shifted away from the centre of your consciousness, which allows you to behave in a humane, harmonious fashion, if you wanna get back to that you have to somehow work through and that’s the god of hellfire; that’s what the god of hellfire is. It’s kind of purgatory in Christian terms or even some of the other religions. And then comes in the next figure, his god brother. It’s not like that. Fire is also aweing. This is the god of pure fire who says, “When you see a fire burning inside your mind’s eye, breathe the meaning of the flames before you let them die.” And then it says, “Twisting, turning, falling, burning, roaring balls of fire; those who see them have no need of guides to spend awhire.” If you can see that and hold it you don’t need gurus and teachers, but [for] most people it’s too difficult; our education doesn’t deal with it, although it’s quite natural.

On that point of education, what about the idea of the musician as a shaman or a hypnotist, the zen teacher?

Yeah, certainly I looked at all those things and saw them when I came into contact with different teachers who I learnt things from, but the work itself is designed to move people through those things depending on how you wanna take this. From one point of view it’s just a show, but if you really watch it it’s all there.

Your first album, ‘The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown’, you decribed as a book of shadows and an inner journey. What were you evoking as yourself as the creator and the audience as the listener?

Well there’s an idea in our culture: we like to take things and put them in a laboratory or somewhere where we can watch them and observe, and it’s been presumed that they are two different functions. One of them is accurate, that’s the observor, but modern physics has showed that even someone who’s observing actually changes what is perceived. So extending that to our show, the audience watch it and, whilst if you look at it, there’s people on a stage and there’s an audience and that starts off as a separating duality, actually all the time we’re joined on another level of consciousness, so any interaction is changing. When the audience watch it and get something, whatever it is it affects the performer on a subliminal level and then things come out that may not normally happen.

What were your experiences at the UFO Club in the very early days?

The UFO Club was the centre of the English underground that was in an Irish music club called The Barney Club. They gave it to the UFO Club for the Friday and Saturday nights, so it was a place where people came if they wanted to not be bound by the normal conventions of what kind of music would be played; what kind of things would be allowed for an audience. So they were open to just about anything happening and if you went in the days when it was pretty radical and intense, you might see a naked poet walking around proclaiming something; a politician over there; a priest might come in…all kinds of different people. There’d be the Floyd, who were experimenting with electronics, Keith Emerson from Emerson Lake & Palmer…and he was getting all sorts of ideas from various people there. There were dance troops; just all kinds of artistic things. There were people experimenting with the original psychedelic light shows based on oil heating up and passing over each other giving different colours. Everybody was learning from everybody else. And that was the beauty of it. If you went into that club you were sure to learn something from somebody who was doing something else all together. It was a crucible of creativity and everyone who went in there learned.

Afterwards the media like to take figureheads and so they come out and say, ‘I created this, I was the one who did that,’ because that’s how you sell things. But in actual fact there was noone in there who wasn’t influenced by everybody else in the club. because you’d play there week after week and you’d do a bit and then you’d see somebody else play something and you’d do it in your own way. We had incredible folk artists: Incredible String Band. Tom Vance came down there…most of the big artists – and from the world of opera and ballet – were down there and politicians of the day. It was just a place where the world was reconfigured without the usual machinations and the idea that maybe society was based on principles that were not finally significantly human. Everybody was looking at new ways of doing things.

What about your own influences visually and musically?

I went to King’s College in 1960; I was supposed to be studying law but I got involved with music and theatre. And in that time I went to some of the more radical new theatres coming up and one of the techniques was these ‘voiles’, as they call them – that was the first time I had ever seen them; that was the first time they were used – and nobody after that bothered with them. We used them in my band in ’72 and now we’ve got the full technology able to take advantage of that. Also I was introduced to a lot of the modern ‘Jazz On A Summer’s Day’ films – Miles Davies, Charles Mingus – and that influenced me a lot musically. There were some of the old films, ‘Battleship Potemkin’, very early Russian movies…all kinds of different movies. So I went down there and I was introduced to all the beatniks.

What about the magical influences?

Ah! Well people who weren’t really into all that would be using ouija boards and different ways of trying to access what would be seen as a magical thing, something coming from beyond death, and sometimes it would happen. There was all of that and then there was one time when we went to a party – this was in the early days in ’67 – and it was the Jefferson Airplane’s party. And everybody was playing Mahjong; it was completely silent. I sat there for about 10 minutes, they were playing away (I got there a few minutes after it started and I wasn’t really part of the game). I was sitting at this table and suddenly over the top of my head came this huge colour illustrated book. It was called ‘The Secret Teachings of All Ages’, and it was all the different magical, mystical [cultures]…the Rosicrucians, the [Ancient] Egyptians and all their magic from all over the world. I met an artist called Mark Reynolds and we used to just talk about all of the Christian beliefs: the devils, the angels, what does life mean and the symbols that came from different parts of the world. We took them and put them on our costumes. There was an audience who was willing and able and wanting all those kind of symbols. And in actual fact, it turned out later that the person who wrote that book, Manly Hall, was the guru of Elvis Presley. Strangely enough it was when he burned down the guru – because Colonel Tom Parker said “It’s him or me Elvis”, so Elvis chose Tom Parker – he was dead in six months. But it shows someone like Elvis, who noone associates with hippies (he wanted to put them in jail) was studying all that stuff. It was spreading and that’s what made governments pretty worried.

Ah! Well people who weren’t really into all that would be using ouija boards and different ways of trying to access what would be seen as a magical thing, something coming from beyond death, and sometimes it would happen. There was all of that and then there was one time when we went to a party – this was in the early days in ’67 – and it was the Jefferson Airplane’s party. And everybody was playing Mahjong; it was completely silent. I sat there for about 10 minutes, they were playing away (I got there a few minutes after it started and I wasn’t really part of the game). I was sitting at this table and suddenly over the top of my head came this huge colour illustrated book. It was called ‘The Secret Teachings of All Ages’, and it was all the different magical, mystical [cultures]…the Rosicrucians, the [Ancient] Egyptians and all their magic from all over the world. I met an artist called Mark Reynolds and we used to just talk about all of the Christian beliefs: the devils, the angels, what does life mean and the symbols that came from different parts of the world. We took them and put them on our costumes. There was an audience who was willing and able and wanting all those kind of symbols. And in actual fact, it turned out later that the person who wrote that book, Manly Hall, was the guru of Elvis Presley. Strangely enough it was when he burned down the guru – because Colonel Tom Parker said “It’s him or me Elvis”, so Elvis chose Tom Parker – he was dead in six months. But it shows someone like Elvis, who noone associates with hippies (he wanted to put them in jail) was studying all that stuff. It was spreading and that’s what made governments pretty worried.

Your other band Kingdom Come didn’t have much of a commercial impact but musically it was very ahead of its time, how do you reflect on that period in your career?

The audience that liked fire didn’t know what it was about and they liked the madness and the flames; if they came and that wasn’t there then we lost that so we had to create a new audience. We experimented with management where the manager was just an equal member of the band and the money was shared out equally with the roadies, all the peformers and the management, but in the end it was too difficult because the whole system of money is set in a different way. Too difficult for us; I think the Grateful Dead actually managed to get it properly working. We got a lot of good critical acclaim…there were people in that band who stayed throughout the whole of its existence and there was a lot of change.

We lived in a farmhouse which in those days is what you did if you were in a band – lived together, worked together and played all day. I also had come back from America with a different view of how things were because they were dealing with direct reporting of the Vietnam war and there were people on the screen riddled with bullets – not a film – and that was just news reporting which they stamped out as far as they could. When you come back and you look at what’s going on in England – in those days a lot of the young people weren’t political at all – it was a welfare state. You could live in a bubble with government money and not have to obey all that much of what was supposed to be becoming why you were able to get welfare, and there wasn’t a problem with people living in alternative ways until the government here realised this could spread – people seem to be liking the idea of it. Some people were saying the whole basis of society is wrong, we should break it down and have play as the basis of it, not duty or work, but play. And they started to say how that would be possible. People said, “Why do I have to work all day? That’s interesting. You’re telling me that financially it can happen?” and they said, “Yeah, this is how you do it.” It’s all made up anyway. Money’s made up. The rules are what keep it doing what it does. So let’s change the rules radically and the government decided they would prevent that and they did.

We lived in a farmhouse which in those days is what you did if you were in a band – lived together, worked together and played all day. I also had come back from America with a different view of how things were because they were dealing with direct reporting of the Vietnam war and there were people on the screen riddled with bullets – not a film – and that was just news reporting which they stamped out as far as they could. When you come back and you look at what’s going on in England – in those days a lot of the young people weren’t political at all – it was a welfare state. You could live in a bubble with government money and not have to obey all that much of what was supposed to be becoming why you were able to get welfare, and there wasn’t a problem with people living in alternative ways until the government here realised this could spread – people seem to be liking the idea of it. Some people were saying the whole basis of society is wrong, we should break it down and have play as the basis of it, not duty or work, but play. And they started to say how that would be possible. People said, “Why do I have to work all day? That’s interesting. You’re telling me that financially it can happen?” and they said, “Yeah, this is how you do it.” It’s all made up anyway. Money’s made up. The rules are what keep it doing what it does. So let’s change the rules radically and the government decided they would prevent that and they did.

And Kingdom Come’s album ‘Journey’, can you tell me about the technical process?

A lot of [the audience] didn’t know what a drum machine was. Some of them would go round the back and search for the drummer. “You’ve got a mic in the room haven’t you?” “No, no, no you press this button here.” And so there was that and (the nearest we could get to [today]), there were projections. We tried to make it like a rock version of a string quartet: everything was balanced so that the drum wasn’t more important than anything else. We were used to playing musical games with each other: take a phrase, this person embellishes it, and soon it changes, changes, changes and that gets you working together in a different way. Then you might put in something that didn’t fit just to see if you could trip up the next [person]. If you work out what you’re gonna play and then if someone does something different, how do you suddenly let go of that and just follow what this new thing is. So we learned all kinds of games to make the music flexible.

But even with that flexibility did you find that you were frustrated at the time?

I was looking for something and so in the process of doing these things I was not arriving at that and, perhaps mistakingly you could say, I decided I had to with the band disband it and go into that [retreat] and find [myself]. and it did take many years for me.

You once said, “The experience we give is alienation in its modern concept of the human mind being removed from its true essential joining point with the emanations of the divine spirit, by entrapment in its own creations of systemic self-perception.” Does your music provide sustenance, a solution to where humanity is?

We have our own solution to it and so whatever it is it comes out in the music. That is the basis of this but then in this one you have a figure that represents someone who’s not entrapped. We [as people] enjoy being trapped. So it’s a question of you present it, and then whoever wants it can take whatever they like from it.

In the end, the heart and the essence of the heart is always still awake, loving…it’s always like that. When we manage to break away from what people expect of us, what we expect of ourselves, there it is, so a journey is only for the mind; the heart is already cured. And the only thing that steps away from it is the ego, because the same mind, after the ego is dealt with, works wonderfully. In the Indian system with Maya and illusion, if you keep looking at it through particularly realistic mind then you’re trapped in illusion and that means the heart in you that’s already there in every moment is always is just what it is. Then if you just stay in the illusion, which can be delightful, in the end you’re still needing to make a journey to get back to that. That’s where religion tries to help, unfortunately for religion it usually gets trapped itself. They try to remove the poetry of it and treat it like facts. Being born of a virgin lady is a poetic concept talking about the heart really, but they try to make it into a fact because that’s the mind they like you to use for your daily [life]. If you’re gonna have real systems from moment to moment and real love you have to find the place where all that is rooted. That’s where you’re rooted.

In the end, the heart and the essence of the heart is always still awake, loving…it’s always like that. When we manage to break away from what people expect of us, what we expect of ourselves, there it is, so a journey is only for the mind; the heart is already cured. And the only thing that steps away from it is the ego, because the same mind, after the ego is dealt with, works wonderfully. In the Indian system with Maya and illusion, if you keep looking at it through particularly realistic mind then you’re trapped in illusion and that means the heart in you that’s already there in every moment is always is just what it is. Then if you just stay in the illusion, which can be delightful, in the end you’re still needing to make a journey to get back to that. That’s where religion tries to help, unfortunately for religion it usually gets trapped itself. They try to remove the poetry of it and treat it like facts. Being born of a virgin lady is a poetic concept talking about the heart really, but they try to make it into a fact because that’s the mind they like you to use for your daily [life]. If you’re gonna have real systems from moment to moment and real love you have to find the place where all that is rooted. That’s where you’re rooted.

The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown’s latest studio album, ‘Gypsy Voodoo’, is available now on CD and digitially.

Photos © E. Gabriel Edvy/Blackswitch Labs.

© Ayisha Khan.

JAZ COLEMAN – THE GREAT INVOCATION

The founder and longstanding frontman of Killing Joke releases his first solo album in the mastercore series; an orchestral interpretation of the band’s music played to the chorus of the St. Petersberg Symphonic Orchestra. The record, entitled ‘Magna Invocatio – A Gnostic Mass For Choir and Orchestra Inspired By The Sublime Music of Killing Joke’, represents a vision for peace in a world brimming on war, an ambition to lift the listener up to a state of conscious awareness and an exploration into Coleman’s own rich classical music heritage. He speaks about his early musical awakening, the battle for world peace and what really happened with the PledgeMusic campaign.

How did you first embark upon this project?

What I do before I start any major project is I dream it first. I’m lucky because I have almost total recall in my head, for example, I can hear music and can score whole sheets of orchestra inside my head. I couldn’t do it in my 30s; I can do it now. I can do it in milliseconds; I know where everything belongs and how you do this is quite simple. Think of your favourite song. You’ve got to be able to listen to it from beginning to end in every detail inside your head. You can practise this and have the ability to shut off extraneous sounds from outside. I go from cafe to cafe – I like grand cafes with high ceilings – and I sit there and dream and think how must it be, how should it be, how should we do it? I just see what turns up and start hearing things internally. That’s how I do it.

And being well travelled too must help get the inspiration…

What’s important is to have a series of contracts in your life. The way I write music is I forget about music; get a life philosophy, fall in love, travel…be in a succession of different cultures so you’re always in a state of shock on every level. By being in a new culture you must be alert, you must have situational awareness; it keeps your mind ticking over. Be in different cultures surrounded by different sounds and noises. When people have too much routine they actually get old quicker.

How did you set about composing the music for this album?

I never work until I feel like it. Normally what I do when I’m composing is I hire a house and get my friends round and then we start arguing or get high…and then I tell everyone to shutup and start playing when I feel like it. So I’ve got an unusual approach to everything. When you’re looking at complex systems you have to reduce everything to their basic components. So once you’ve got a six-part harmony it’s just a question of placement. I did that in milliseconds in my head.

I never work until I feel like it. Normally what I do when I’m composing is I hire a house and get my friends round and then we start arguing or get high…and then I tell everyone to shutup and start playing when I feel like it. So I’ve got an unusual approach to everything. When you’re looking at complex systems you have to reduce everything to their basic components. So once you’ve got a six-part harmony it’s just a question of placement. I did that in milliseconds in my head.

It started early in my life because I started a choral and classical tradition when I was 6, so by the time I was 13 or 14 I was very successful with international festivals – singing and violin – so I was set for classical music. And then of course rock ‘n’ roll happened and I was a punk. I went back to classical music around the age of 22 and then studied intensely for another 10 years – orchestration this time – so I could write effectively for any instrument. From there the rest is budget…when there’s no budget I still use a pencil and paper. I get tables and mark the music out with pencils and the piano.

Did you have to go to Russia to consult the orchestra?

I sent my scores way ahead of time to the conductor. When you’re working with a full chorus with a symphony orchestra everything has to be recorded together. So when you’re dealing with an ancient Sumerian language thats 1400 years old and no one knows how to pronounce it (I had to consult with the professor of etymology at St. Petersberg University and he educated the choir on pronounciation before my arrival) that’s the importance of getting the score ahead of time. You have to get one score to the choir master with a piano rendition and one score to the conductor.

When I was in Russia I normally work with the state orchestra of St. Petersberg. We were pushed up to Russia’s oldest orchestra suddenly under the climate when all the British diplomats had been expelled. Everything in Russia goes through the state. Everything is centralised and I’m no exception to that; I worked through the minister of culture. I’m one of the few Western artists that work in Russia with the current climate of Russiaphobia manufactured in the West (because they want a war; they think Jesus is gonna turn up quicker). The world is in a terrible situation. We’re looking at such a bad year next year that I hope you and I are still alive.

When I was in Russia I normally work with the state orchestra of St. Petersberg. We were pushed up to Russia’s oldest orchestra suddenly under the climate when all the British diplomats had been expelled. Everything in Russia goes through the state. Everything is centralised and I’m no exception to that; I worked through the minister of culture. I’m one of the few Western artists that work in Russia with the current climate of Russiaphobia manufactured in the West (because they want a war; they think Jesus is gonna turn up quicker). The world is in a terrible situation. We’re looking at such a bad year next year that I hope you and I are still alive.

If you add onto that the fact that we no longer live in a bilateral world of the USSR and the USA in this new cold war, it’s a much more dangerous situation. We’re heading for what’s termed a complex systems failure – we’re going into an area of unforeseen consequences starting very, very soon. And I’ve seen this coming all my life. I see my work with the symphony orchestra in Russia and my work with the United Nations and Lucis Trust as a way towards world peace. Last week I was a guest at the UN. The US hasn’t paid its subscription to the UN so this is the last month that everyone in the UN gets paid – it’s fallen to bits. That’s how bad the world is now. And if we’re going to go into war with China and Russia it’s because we have a public that’s no longer prepared to put their balls on the line and speak out against this. Elon Musk is certain that war is gonna happen and bear in mind that one nuclear weapon is 65-miles radius. One on London takes out Madrid, Berlin and Reykjavík and everything inbetween. We’re looking into the abyss of extinction or setting evolution back 50 million years. How does it feel?!

I found the track, ‘The Raven King’, dedicated to your late friend, very uplifting and forward moving.

It is, that’s right. To summarise on that, “The dead live by love, consciousness survives death” is [a quote] that my brother Dr Piers Coleman made (he’s one of the US’ top scientists and an atheist may I add not a mystic like me). I always talk about the dead in the present tense. If you like, Paul can be here now, he can sit in that chair next to you if you like, smiling at you…probably looking at your arse!

I wanted to lift people’s spirit up to planetary consciousness, nothing less. I listen to it because it lifts my spirits. By listening to it I can connect with the divine. Unless we experience planetary consciousness we’re looking at total extinction.

Why did you choose to record this particular selection of tracks?

‘Cause they’d be the last tracks you’d ever think of…and to annoy my colleagues. But I make sure everybody gets the same money. It’s an important thing…one of the things that I’ve learned through Killing Joke is that communism works. We work for each other because we split everything equally; we’re collectivists not marxists.

What do you mean by ‘gnostic mass’ and The Great Invocation?

Atheist is I don’t believe; agnostic is if something happens to me maybe I’ll believe there’s forces or a divine and gnostic is I have experience and therefore I have arrived at certain conclusions. The gnostic tradition generally speaking is mostly misunderstood by the Judaic or Christian viewpoint because essentially we see the god of the old testament as the dark god; the demiurge. If you have a look at the old testament, if Yahweh was a person they’d be tried in the International Criminal Court for genocide. Yahweh is the dark god; an inorganic predator. It’s an apocalyptic cult.

Atheist is I don’t believe; agnostic is if something happens to me maybe I’ll believe there’s forces or a divine and gnostic is I have experience and therefore I have arrived at certain conclusions. The gnostic tradition generally speaking is mostly misunderstood by the Judaic or Christian viewpoint because essentially we see the god of the old testament as the dark god; the demiurge. If you have a look at the old testament, if Yahweh was a person they’d be tried in the International Criminal Court for genocide. Yahweh is the dark god; an inorganic predator. It’s an apocalyptic cult.

The Great Invocation is the mystical prayer of the spiritual arm of the United Nations. This project was doomed, but when I started using The Great Invocation, mysteriously the funding came.

Can you talk about the origination of your interest in classical music?

Plato said, “All knowledge is remembering,” and I’m inclined to agree with that. My relationship with music is like an arranged marriage. When I was four and my brother was six it was decided that he do science and I do music so it’s never really been much of a choice for me. What did surprise my atheist parents is when I embraced the English choral tradition. I was very lucky because from the age of seven before I was in Killing Joke I had a teacher who was amazing and he taught me violin, a little bit of conducting and choral tradition, and this was a huge passion of mine.

My childhood was singing in the cathedrals across England with The Royal School of Church Music and then missing loads of school by going on chamber music courses and to beautiful manor houses across England. So I had an incredible childhood and it culminated in winning the Cheltenham International Festival and other international festivals, and that was before puberty kicked in. Then I started listening to rock music and that happened overnight. But before that I remember Brian Jones…my grandmother was a mentor for Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones. So he was a regular visitor to my house up until I was seven years of age.

What were some of the epiphanies and milestones that shaped the person you are today?

What were some of the epiphanies and milestones that shaped the person you are today?

Well the first epiphany happened in Montserrat in Spain when I was 4-and-a-half or 5-years-old. I had a vision that changed my life: that I must do music and I’m protected by a goddess. I wear the Black Madonna around my neck. That experience shaped my entire life. I was born into an atheist family but I’m a mystic. There are many milestones…I don’t know where to continue, we’d have to have a very long talk. There’s been many huge milestones.

What about your time in Egypt?

Egypt started in 1981 for me. I went there because I’m fascinated by the antiquities (even back then there was a lot of demonisation of Arab culture through the media so I found it a big shock there was such a warm welcome and people were really wonderful, totally different to my preconception of the place). But what I found was the people and the music and eventually that resulted in studying for a short period in Cairo Conservatoire. And then recording in the Great Pyramid…the experience we had there was that we were covinced the pyramid is many things but one of the things it is is conscious technology. Our recording engineer fell asleep in the King’s Chamber and when we started the ritual there he saw thousands and thousands of alien eyes. They’re linked to the people who built these places.

What happened with the PledgeMusic campaign? Fans never received a copy of the release, what do you want to say to them?

[PledgeMusic] were under – it didn’t even cover a third of it. What I didn’t say is that the management I had at that time refused to hand in any accounts, but I never had any money anyway. Was there any money? What happened? And then Pledge went under. I dont want to talk about legal cases but this project was started by a dubious ex-manager who tried to stop me even having access to Killing Joke’s Facebook. A very nasty piece of work actually, and he set this up knowing it would fail ’cause he had a grudge with me and I had a massive falling out with him. And so he said if we do this with Pledge I can peel off 10 grand and put it in my pocket. Well that didn’t happen. What happened was I got into massive problems.

The next thing I know the very same manager says Jaz Coleman’s gonna be doing the Dudley/Coleman album, ‘Songs From The Victorious City’, to raise money to finish the recording. Without consulting me, they wouldn’t give me any budget to fly any Arabic musicians over to do it with and it would have run at a loss anyway. The whole thing was a setup! I was set up to fail, no preliminary budget was done and if it was he knew it would fail. It was done to set me up. And they lost the battle ’cause [the album] happened…and when I started using The Great Invocation and the occult forces thereby, I had my first dream in 25 years: I saw an orchestra in the Tsars palace. Two days later I had the funding and I was on my way.

I’m no longer with the manager that wouldn’t give me any accounting…it’s a miracle that the recording went ahead. I’ve done what I can [with the Pledgers Q&A event], the record came out and the profits of the record are going to an NGO of my choice. So if it makes [the fans] feel any better I didn’t get any money either.

‘Magna Invocatio – A Gnostic Mass For Choir and Orchestra Inspired By The Sublime Music of Killing Joke’ is available now on CD, double vinyl and digitally.

All photos (except colour) © E. Gabriel Edvy/Blackswitch Labs.

© Ayisha Khan.